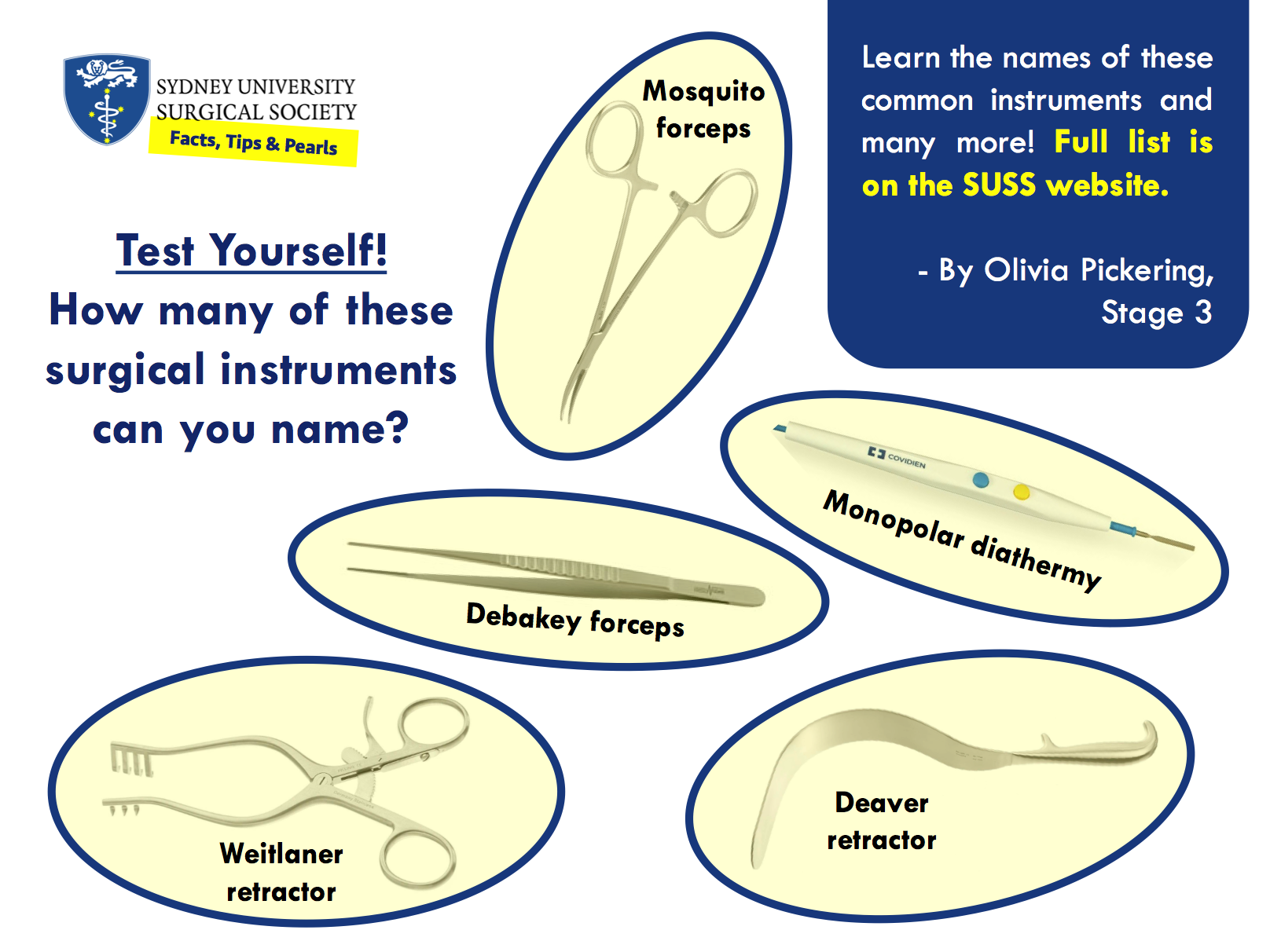

Surgical Instruments

Instruments for Cutting

Forceps

Suction

Retractors

Electrosurgical Instruments

Dr Eric Levi on his favourite operations, future challenges for surgery, and social media in medicine.

by Alon Taylor

Alon Taylor: Who are you and what do you do?

Dr Eric Levi: My name is Eric and I’m an ear nose and throat, head and neck surgeon. I did my medical schooling and surgical training in Melbourne. Right now, I’m in Canada on my first of three fellowship years, currently subspecialising in head and neck surgical oncology, facial plastic and reconstructive surgery. The next two years will be in other countries in different subspecialty ENT areas.

AT: How did you settle on ENT surgery?

Dr EL: I suppose it’s through a process of discovery. Let me say this at the outset: I am a doctor first and a surgeon second. Every specialty within medicine and surgery is fascinating, interesting, and noble. There is not one specialty that is better than another. However, it is true that there are probably a few specialties that are better suited to you. As a medical student I was fascinated by emergency medicine, then neurology, then paediatrics, then obstetrics. But the more surgical rotations I did, and the more I studied surgery, the more I was drawn to it. It was at internship that I made up my mind to do surgery. I reserved my decision till then because I wanted to taste the life as a surgical intern and see first-hand the life of a surgical registrar and a surgeon. What you see as a medical student is different to what you actually see as a working doctor. The romantic notions of surgery you hear as a student are quickly offset by the realities of working in a high-pressure surgical unit day in and day out from 6 am to 8 pm with very few breaks. Once I made up my mind to do surgery, the choice of which surgical specialty was a little easier. I got to be a resident in almost all of the surgical specialties during basic surgical training and tasted the good and bad of each. I fell in love with ENT and its community of surgeons. I felt that ENT was the one specialty that suited me most.

AT: Best and worst parts of your job?

Dr EL: Other than earwax and tinnitus, the worst part of my job (and I think most surgeons would agree) is the demand for a total commitment of time, effort and intellect. Surgery is like an all or nothing phenomena. It demands all of you. The arduous training, the long hours, the physical expectation, the intellectual stamina and the emotional resilience required to be a surgeon is not to be taken lightly. When I do my 12-hour-long cases, I have to block out everything else and focus on that patient. When I’m on call, I need to be able to get up at 3 am, drive to the hospital and know that I can safely do a procedure. You don’t do shiftwork. You’re on almost all the time. Your patients expect a lot from you. Other clinicians expect a lot from you and the public demands a lot from you.

On the flip side, that demanding aspect of surgery is also the best part of my job. Some of us thrive under stress. We enjoy challenges. I get a real kick out of doing complex procedures, or just out of doing simple procedures well. I love my patients and I love learning about my patients in clinic, but if you were to push me hard I’d have to confess that I’m a surgeon simply because I really love surgical challenges and surgical problem-solving. There are some problems that can be fixed through expert craftsmanship. And that’s the best and most satisfying part of my job: a tangible difference in the lives of the patients I operate on.

AT: What is your favourite operation to perform and why?

Dr EL: In answering that question, let me also mention that actual surgery forms only a part of what we do as surgeons. The bigger part of surgery happens outside the operating room. There are a lot of non-surgical things we do as surgeons. So, my favourite operation would be my next one. I love the variety of procedures that ENT offers me. I remember the tracheostomy I did on a premature neonate that weighed a little heavier than my MacBook Pro. I remember fondly the cochlear implants on children and adults. I love the total nasal reconstruction. I also love the skullbase tumour resection, the craniofacial resection, the transphenoid pituitary, the acoustic neuroma, the orbital decompression, the jaw-neck resection, laser pharyngectomy, vocal cord injection, orbital exenteration, maxillectomy, carotid body tumour, dacrocystorhinostomy, laryngopharyngectomy, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, stapedectomy, ossiculoplasty, rhinoplasty, blepharoplasty, local flaps, free flaps. Also the thyroids, parotids, tonsils, grommets, endoscopic sinus surgery and everything else in between. You just got me started there. Sorry.

AT: What were the challenges you faced on the path to where you are today?

Dr EL: I learned that I needed to accept rejection and that I can’t have it all. I knew that the training was demanding and arduous but I didn’t quite realise how hard it was until I was in it. Feel free to call me if you wanted to hear how many times I failed the job application, the interview, the selection, the exams, the research proposals, the manuscript submission, etc. Accepting rejection has become a normal part of surgical training for me. I also learned that I can’t be everything I wanted to be: husband, dad, traveller, social animal, party goer and surgical trainee all at the same time. Something’s gotta give. I couldn’t go to all the holidays, concerts, and parties that I wanted. I had to miss out on some of my wife and kids’ significant moments due to exams, conferences, emergency cases and the like. Thankfully, I don’t do surgery alone. I am where I am today because of the support of my loved ones. Now that I am a fellow and a consultant, it gets a little easier as I have a slightly better control of my days. It still requires a huge effort to maintain work-life harmony though. A constant evolving challenge. A worthwhile challenge. One of the simple philosophies of life I hang on to is this: if you love your work, good work will come to you. Love what you do (no matter how challenging it is) and then you will get to do what you love.

AT: What do you see as the major issues facing surgery today?

Dr EL: There have always been and there will always be many issues facing surgery because of the reality of the world we live in. Some major issues include bullying, harassment, gender equality, work safety, resource allocation, surgical selection, training competence, ethical responsibility, global surgery, etc. Many other experts can speak directly and with greater depth about those issues. Some may disagree with this, but in my opinion, the biggest challenge affecting surgeons individually and as a profession is the problem of surgery losing its clinical heart. Surgeons are increasingly reduced to mere proceduralists and technicians. Clinical decisions are being taken away from surgeons and restrictions are imposed upon what we do by non-clinicians. Everything from procedure duration, operating costs and length of stay are measured as if surgeons and patients were indistinguishable factory line products. The long-term effect of this is that surgeons will be seen as skilled but uneducated technicians. This will be unfortunate because there’s so much clinical wisdom and expertise outside the operating theatre that is required to be a good surgeon. Performing an operation is only a part of surgical competence. Why the operation, getting the diagnosis right in the first place, when, where, which technique, what to do, what not to do, when not to do the operation, what happens before and after the operation, rehabilitation after the operation – those are even more significant surgical competencies. That kind of surgical wisdom comes from knowing the heart and essence of surgery: that surgeons are first of all doctors, but doctors who happen to also be trained in the use of the scalpel.

AT: What advice would you give to medical students with a budding interest in surgery?

Dr EL: Very few of us know that we are born to be a cardiac transplant surgeon, paediatric spinal surgeon or epilepsy surgeon. For the rest of us, keep your options open. Don’t be infatuated by media descriptions of surgery. Don’t eliminate options too early. Taste the life of surgery before fully committing to it. It’s a costly journey financially, physically, emotionally, socially. Make sure you’re willing to pay the price. Decide firstly if you want to be a surgeon at all. Once you decide on surgery, think about what problems you like solving. Don’t focus on the operations themselves. Think about what kinds of problems excite you. If possible, get a feel of the specialty community. Is there much collegiality in that specialty? Will you like the people you will be working with for the next 30 years?

AT: You are very active on social media. What do you see as the importance of social media for a clinician?

Dr EL: Now this question deserves a whole lecture, seminar and textbook in itself. I won’t go into too much detail as I and many others have written extensively on Social Media in Medicine elsewhere, but I will say this: I’m on social media because my patients and trainees are already there. I need to understand what kinds of information are being fed to my patients. I need to understand the current challenges facing my trainees. Social media helps me to listen in on these conversations. Once in a while I get the privilege of helping others through social media in the form of education and engagement. That’s nice, and it goes back to the essence of our roles as doctors. We are teachers and helpers. We sometimes get invited to engage with others and help them lead better lives.

Professor John Cartmill on his path into surgery, work-life balance and how to approach surgeons for shadowing opportunities

By Nathaniel Deboever

Nathaniel Deboever: Which pathway did you take into the surgical field, and would you do it again?

Professor John Cartmill: “I wouldn’t change my pathway, and I don’t think I could have done it differently. Are you familiar with the term teleology? It has the same word root as telomere, from the Greek telos, meaning end or purpose. In other words, a career progression all makes sense looking back, but in prospect who would have known or been able to guess? It feels as though it was more of an evolution; variation and selection, pursuing things that really interested me rather than things that were expected of me (variation). Opportunities came up that those interests had prepared me for (affordances), opportunities I was prepared and excited to take (selection). That process continues of course!

Surgically, it probably started when my father (a cardiothoracic surgeon) taught me to tie surgical knots and my mother demonstrated the correct way to pass the tomato sauce at the dinner table – the firm ‘instrument pass’ that feels a bit like a handshake. There was no pressure one way or the other and it really only occurred to me that I might be a surgeon when I was in second or third year of medical school. I saw a surgeon, David Glenn, performing a triple bypass for pancreatic cancer. I just thought that it was the most beautiful thing I had seen. It was on a patient that I had come to know, she had a very nasty pancreatic cancer, and was going to die, but he improved her lot in the most profound way. I was very moved by it, and I wanted to do it. From then on, I spent a lot of time in the operating room, taking it all in, taking some knocks from scrub nurses and other people who thought I was in the way, but you know that’s where I wanted to be and I would learn people’s names and do all the little things and let it be known that I was interested, volunteer to be an extra set of hands when anyone was needed.

I struggled a bit with the surgical primary College exam (as many do!) and ended up taking time away from the hospital to pursue a Masters in molecular biology while I studied, in the same lab (Cris dos Remedios) where I had enjoyed a BSc(Med). I ended up with some publications, a little bit by accident. I didn’t mean to be an academic surgeon but before I knew it, I had a couple of publications and no one else did, so my CV looked better than the next guy.

A little later on, once I was on the training scheme, I developed an interest in medical error, which at that time no one else was really following. I developed that interest because I thought I was blaming myself for things going wrong, for errors, and I just think I was particularly aware of it and sensitive and didn’t like it happening so I wanted to understand why. An important mentor drew my attention to the cardiothoracic literature which was being influenced by aviation, mining, and industrial safety at the time. So again I had an ‘extra string to my bow’ as a surgical trainee at the time, when it was not all fashionable. I think this is what going off the beaten path is all about, following your passion. That makes it easy.

So then I was a surgical trainee, and I was also very interested in laparoscopic surgery. In the 1980s, lap-choles came around and revolutionized gallbladder surgery. I thought I could transfer some of those advantages to colorectal surgery so I followed laparoscopic surgery to the United States where I worked as a fellow with a group of pioneering laparoscopic surgeons in Minneapolis. Because of my interest, I was invited to spend six months working as an engineer with a biomedical company (Ethicon in Cincinnati). I worked there between a laparoscopic surgery fellowship and a colorectal fellowship at the Cleveland clinic. As a result of that, I got a few patents, so my CV started to look a bit different and special, and after all of that, I was able to come back to Australia as a colorectal surgeon.

My interest in error had developed into the emerging field of neuroscience, communication and teamwork and I was pleased to help develop the PPD (personal and professional development) strand at Sydney University. Again because of my interest in error and people working together, I was introduced to Macquarie University linguists (another unconventional interest for a surgeon) David Butt and Alison Moore and became impressed by the university so when Michael Morgan asked me to help build the fledgling Australian School of Advanced Medicine.. I jumped at it. We are now a full faculty and I expect that some of you reading this will join us at MQ for training and work.

As I said, the process continues.

Through all of this I have continued to work at Nepean Hospital in Sydney’s west.

ND: Could you tell me a bit more about your involvement in the topic of medical error?

JC: I trained in an era when the most frequent response to a medical catastrophe was to find someone to blame and I always felt that I wanted to know how and why it had happened. At the time that would have been called an excuse, but for me it was an explanation, which meant that if we understood it we were less likely to repeat it. So I made it my business to find out and it has been a very interesting obsession (I guess that’s what makes something an obsession: interest). I came back to the medical faculty at Sydney after my time in the States as a senior lecturer. I think this was around the time when the PPD curriculum was being written and I was asked to incorporate my medical error work into that, and I had also decided that it was what I would do. It was just the perfect opportunity to explore medical error at all of its levels. We were encouraged by some forward thinkers in the Health Department to spread the word and I formed a company called ErroMed with Don Wynn, a Qantas captain, anaesthetists Richard Morris and Stavros Prineas, psychologist Stewart Dunn, and physician Darryl Mackender. We had some success with that, and learned at lot. ErroMed continues to do good work internationally although I am no longer a part of it.

I became very interested in how adults learn as a result of designing these courses and working with my ErroMed colleagues who were all extraordinary teachers.

More recently I’ve been pleased to meet like-minded surgeons as we have developed the Training in Professional Skills (TIPS) course for the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons.

ND: So how did you end up at Macquarie University?

JC: I was asked to join largely because of my research in teamwork and medical error. At that time all of the neurosurgeons in New South Wales had taken the ErroMed courses, and so I was reacquainted with Professor Michael Morgan, the foundation Dean of the Australian School of Advanced Medicine at MQ (now the FMHS). I had enjoyed a wonderful collaboration with David Butt and Alison Moore looking at Systemic Safety so I was very pleased to join the staff of the University. The ongoing development of the Faculty, the Macquarie University Hospital and my role within it has been wonderful.

As your career develops, you move from someone who hopes to be appointed, to someone who gets appointed and ultimately you become involved in the appointing. If there was a rule of thumb it would be to always appoint someone who is better than you are. Then you get to work with them and that’s really awesome because they bring you on too. I have had that experience particularly with Tony Eyers, Anil Keshava, Matt Rickard and Andrew Gilmore, all talented colorectal surgeons. They are super people, we all work together, and we are better because of it.

Macquarie University is a very well run university. That is why they have been able to finance, build, staff and have their hospital succeed as part of their Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. No other Australian University has done this.

ND: Now, what about work-life balance? Could you talk a bit about that in the life of a surgeon?

JC: Better to not ask me about work-life balance! It’s a thing that I have not been good at, and I have needed professional help with it. At times I have been so single-minded, nothing else mattered. That is one way to succeed of course, and to some extent that uncompromising passion is necessary – at least it was for me. I think that if you find yourself completely foregoing pleasure, it should be a warning sign and you might need to go see somebody about it. That sort of workaholism is much better understood now at a psychological level than it was when I began surgery. I am not sure it is something you should ask a surgeon for advice on. Deep down, it has to do with personality types, it’s just that the sort of people that often succeed at surgery can be uncompromising and might overdo it. I am not saying that’s right or wrong – it certainly makes for an interesting and useful life – but try to do it with some insight!

ND: Is there anything you wish you had done differently with regards to work-life balance?

JC: Probably. It’s a regret that I haven’t been a more supportive husband, but I’ve been fortunate to have an extraordinary wife who has made significant career sacrifices for me and for our children. I regret that. You know, there I was thinking I was making sacrifices working hard and so on but she was making sacrifices that were just as profound, probably more so. I have two fabulous children that do know me, I did go to speech nights, I usually went to parent-teacher interviews; you know, I did drive to school once a week, but with hindsight I think I could have done more without compromising the surgery.

ND: So with regards to having a family along with pursuing a career in surgery, do you have any advice about that?

JC: My advice would be to go for both. A surgical career does give you some important advantages when it comes to raising a family. You are a pillar of the community! And so you’re the sort of person who should be having a family if you want one, you’ve got good values and principles that are strong, and financially, you become a good provider.

The College is open minded about all of this and you will find advice and even the opportunity to take breaks from training or share a training position.

ND: Changing the topic a bit, do you have any advice for medical students aspiring to be a part of the surgical field?

JC: I would say I was excited for you but do not compromise. I have students that came to me asking for advice, knot tying or needle holder tutorials and so on which I always enjoy – but when they came back, it is so clear whether or not they’ve been practicing. These simple techniques; one and two handed knots, left and right handed, needle holder palmed not restricted by finger holes are not arbitrary, they are part of the surgeon’s vocabulary, the way you will make your mark on the world – or not. What can I do? I can’t practice for them. The sooner you start your ‘ten thousand hours’, the better. On the other hand, if you have been practicing, if you can tie the knot when it is offered to you in the theatre then it will make a big impression. I can still name those students who showed me they could do it and I have enjoyed watching their careers develop since.

The theatre is a complicated, wonderful, consequential space. The theatre nurses rule there, as they should, and they will respond well to intelligent questions, offers of help. Don’t wait to be asked to write your name on the white board. Take it all in, be humble, being in that space at all is a privilege. Answer the telephone if rings – don’t just stand there – “Theatre 6, Nathaniel speaking, how can I help?”.

ND: What about advice on how students should approach surgeons for guidance, and teaching opportunities?

JC: Be sensitive when you ask us. This comes down to human factors and a bit of emotional intelligence. If they’re looking like they’re thinking about something else, don’t ask them. It’s a job that often carries a fair bit of cognitive load. For a surgeon, a good hint that they are open to hear from you is when they go non-clinical – start to talk about something else, you know, the cricket, or a movie they saw, when they begin to close an operation, or at the end of a tutorial or lecture, when they’re not in a rush. Give them a minute as they take off their gown to check their phone and so on. Follow them into the tea room. It should be self-evident. Sometimes you can be a little bit blind to those subtleties when you are nervous, so I would just say use your emotional intelligence (be mindful). You could try approaching the secretary, and be very very nice to him or her. The surgeon wouldn’t be where they are without that secretary. If they are a good secretary, and they invariably are, you are essentially speaking to the same person.

If it’s the surgeon themselves you are asking you could do worse than say “I’m a medical student and I’m interested in surgery, I’m really interested in what you do. Can I spend a day with you when I’m next on holiday?” You know, you’re making a proposal, you should dress like you mean it, wear a name badge, stand up straight, look them in the eye, pick your time; all advice your mother or father would give you.